by: Laura Yares, Michigan State University, and Sharon Avni, City University of New York

Our current project, Jewish Learning in Cultural Arts contexts, questions the prevailing assumption that meaningful Jewish learning needs to occur in formal, outcome-driven contexts. We hypothesize that episodic encounters with cultural arts, including music festivals, book clubs, and museum visits, also offer deep and impactful educational experiences through which Jews can learn not only about Judaism and the Jewish community, but also about themselves as Jewishly identified people. Our project was conceptualized around a relatively traditional program of ethnographic fieldwork and other qualitative methods. In 2019, we began with a pilot study investigating young adult visitors to Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History. In early 2020, we had imagined doing ethnographic observation of a film festival, interviewing participants in their homes and at cultural events, and attending workshops for Jewish visual arts.

The COVID-19 pandemic put an obvious wrench in our plans. Instead of being able to observe participants at a communal film festival and capturing the kinds of engagement and learning they were involved in, as researchers we were stuck, like many of our participants, in our individual homes. And we were watching a lot of television. However, it quickly became apparent that this setback was in fact an opportunity, and that pivoting to include digital media as a site of Jewish learning could open up opportunities for asking our questions in the digital context.

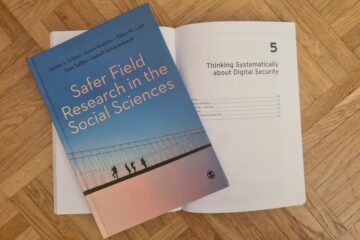

Shtisel Diaries audio app. Photo by authors.

At the end of March 2020, when the pandemic lockdowns went into effect in the United States, we started hearing about Saturday Night Seder. A virtual event, it was scheduled to be broadcast online on the internet-media company Buzzfeed’s YouTube channel to mark the third night of Passover on April 11, 2020. Part-seder, part-fundraiser, and part-Broadway ensemble, Saturday Night Seder offered a lighthearted celebration of the Passover story loosely following the traditional order of the Haggadah – the text recited at the Passover Seder that includes the narrative of the Jewish exodus from ancient Egypt. The production featured stars from stage and screen as well as celebrity rabbis, and authors who filmed short clips in their own homes using I-Phones and personal cameras, woven together by a veteran production team. As of April 2021, the broadcast had raised over $3.5 million for the CDC Foundation COVID-19 Emergency Response Fund, and had been viewed over 1.5 million times on YouTube.

In addition to the transcript of the broadcast itself, we were able to collect data from various sources. As many of the creatives and performers involved in this production were furloughed from work obligations which had been cancelled due to the pandemic, they had time and were willing to speak with us on Zoom about what it meant to celebrate Jewish ritual time for an international internet audience. Had it not been for the closure of studios and performing spaces due to COVID, the producers and creatives would not have been able to take on SNS, nor would they have had time to speak with us about the production. Shifting our attention to the consumers, we also looked to social media, and specifically Twitter and YouTube, to capture the viewers’ experiences: a data set that included 2000 tweets and over 1800 YouTube comments. Though Saturday Night Seder was widely viewed by people isolated in their individual homes, the conversations about the broadcast that ensued on Twitter and YouTube opened our eyes to the potential of social media to enable collective conversations about cultural arts products. This was a new method of data collection for both of us, and we learned a lot about using social media for ethnographic research.

With this new perspective in mind, we turned our attention to another emerging media phenomenon. A new television series from Israel, Shtisel had been recently added to Netflix and was being discovered by Netflix customers looking for new shows to stream from their homes as they were stuck indoors due to the pandemic. Shtisel explores the lives and travails of an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family living in current-day Jerusalem. Filmed in Yiddish and Hebrew with options for English subtitles it was, to be perfectly frank, an unlikely recipe for a commercial success for an American audience. Nonetheless, we both recognized that this show was garnering a lot of interest in the press. We also noticed in our own Facebook feeds that a site called Shtisel – Let’s Talk About it was being widely promoted. We contacted the founder and discovered that she and two of her friends from Detroit, Michigan had founded the site in 2019 as a platform to discuss their mutual interest in the show. Never did they expect their intimate site to explode in popularity the way it did. As of March 2021, the group had over 25,000 members with a growing number in anticipation of the third and final season.

We started our digital fieldwork by focusing on the Facebook group alone. We conducted interviews over Zoom with the group’s founders, and scraped, coded and analyzed postings contributed to the site. Integrating theoretical frameworks from digital religion studies as well as the study of fandoms and fan culture, we thought about the various ways that social media serves to facilitate modes of connectivity that bring viewers together in a collective conversation around a television show that is experienced, for the most part, asynchronously and individually, in viewer’s own homes.

Then came an announcement from Netflix. The third series of Shtisel, which had already streamed in Israel, would be added for viewers around the world on March 25, 2021. It was clear that we needed to find a way to virtually enter into people’s homes, and capture their thoughts and feelings as they watched each episode of the new series. Completely unconnected to our project, Laura Yares attended a presentation at Michigan State University by Betsy Stone and Suzanne Long describing their work on MI Diaries, a multi-year project analyzing language change in Michigan. To overcome the limitations imposed on recording participants in a lab due to COVID-19, they had developed an audio diary app. This data collection tool allowed participants to record audio diaries in response to a given set of prompts that were built into the app screen. A few conversations later, and it was apparent that with very little change to the coding of the app, we could use it as a tool to collect audio diaries of viewers as they watched Netflix. Shtisel Diaries was born.

We used the app to record people talking about their responses to each episode of the show. After viewing, they came to the app and recorded a diary in response to a couple of supplied prompts. We wanted to capture people’s rambling thoughts, musings aloud, and on the fly googling as they watched the show in their living room. We could have asked people to write written responses or participate in a focus group. But as much as possible, we wanted to capture the immediate responses of viewers as the credits rolled on each new episode – to allow viewers to think out loud about what they saw and heard, and to capture that on tape. Speech recognition software built into the back end of the app automatically transcribed the audio files, so that we could code the transcripts to analyze various topics and themes.

In the first week of the new series, we collected over 300 audio diaries from viewers across the world. Diarists talked about the principal characters in the show, all ultra-Orthodox Jews. They wanted to know why they dressed as they did, why they ate certain foods, why husbands and wives slept in different beds, and how they prayed. They asked about divisions between Jews and non-Jews, as well as between different kinds of Jews in Israel. They wondered about language as they noticed that some characters used Yiddish, others Hebrew, and others switched between the two.

We are still collecting data, and anticipate coding and analyzing hundreds of diaries over the coming months. It is clear, however, that as viewers watch Shtisel, they engage in rich and nuanced educational experiences. On the Facebook site, they ask questions of one another. Through the diary app, we see viewers engaging in more personal processes of speculation, and elaborating on the questions that are raised for them by each episode of the show. While we did not anticipate deploying digital fieldwork tools and methodologies to research internet broadcasts and television shows as vehicles for religious and cultural education during 2020, it has undoubtedly yielded rich and compelling data.

Our original plans for our project on Jewish learning in the cultural arts were dramatically altered by the COVID-19 pandemic, but in our need to adjust we discovered opportunities that opened up to us new ways of thinking about this research. We have been able to think deeply about the role of entertainment in creating low-cost accessibility to Jewish topics in the public domain, and about the role of social media in creating learning communities around them. We have also learned just how interreligious such settings can be. Over a third of our diary participants identified as non-Jewish, while the Jewish participants ranged from ultra-Orthodox to secular and cultural Jewish identifications. While we originally anticipated focusing on Jewishly identified viewers and participants, imagining that a few non-Jewishly identified persons might also have some interests in Jewish popular culture, it quickly became clear to us that significant numbers of non-Jewishly identified people are not only interested in Jewish cultural arts, but are engaging in social media communities to discuss their interests. We have learned that cultural arts, and the online social media networks that form around them create vibrant communities for interreligious learning, where religious outsiders not only learn about a tradition that is not their own, but reframe the terrain in important ways for insiders to the tradition as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic also encouraged us to look at new methodologies and new theoretical fields, including digital religion and fandom studies. Our own ethnographic training focused on in-person data collection methods, and we would likely have had little impetus to step outside that prism and consider the possibilities of an audio diary app for ethnographic data collection if it had not been for the social-distancing mandates imposed by the pandemic. Given the success of this project, we are now involved in a series of initiatives to expand the app so that it can be used by other researchers at other institutions.

We eagerly look forward to being able to observe and talk to people at a music festival in the near future again, but among the many lessons we have taken away from this project is a reminder to think creatively about how technology might help us to access more intimate conversations as well.

Funding Details

This project is supported by the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Studies in Jewish Education, at Brandeis University.

Biographical Note

Laura Yares is Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Michigan State University. Her work explores Jewish education as a site for understanding the ways that Jews have constructed and continue to construct understandings of self, community and other. Her current research includes a book project exploring the growth of Jewish Sunday Schools in 19th century America, and a contemporary ethnographic study analyzing Jewish learning in cultural arts spaces.

Sharon Avni is Professor of Academic Literacy and Linguistics at BMCC at the City University of New York (CUNY). She is the co-author of Hebrew Infusion: Language and Community and American Jewish Summer Camps, and is a research affiliate at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Studies in Jewish Education at Brandeis. Her current research includes modern day Hebraists in the United States, and Jewish learning in cultural arts spaces.