So much of what we do as researchers relies on a foundation of trust built over time with the communities where we carry out research activities. When mutual trust is present, we are invited into the lives, minds, and networks of our research participants, which helps animate our research questions. For scholars who use community-based participatory research methods, this means that research is better able to inform practice and achieve meaningful outcomes. For scholars who use process tracing methods, mutual trust may mean special access to archival documents, leading to a deeper knowledge of potential intervening variables, or a more robust understanding of causal mechanisms. For other qualitative researchers, perhaps especially ethnographers, mutual trust means that when researchers promise respondents confidentiality, interviews can be more honest and unfiltered, which may enhance a scholar’s ability to answer research questions.

Given these dynamics, what happens when we are constrained, as we are during the pandemic, to building trusting relationships virtually? How do we maintain relationships with the communities where we research? How might we be able to begin new relationships virtually?

While cacao season was in full swing in the rural areas along the DR-Haitian border…

…my mother and I took a mid-day stroll across a frozen Minnesotan lake.

I find, predictably so, that building relationships with a new research site is challenging to do virtually, while maintaining trust is slightly more straightforward. Contacts I had known for years maintained the steady stream of WhatsApp greetings as the spring and summer (in the northern hemisphere) wore on, sharing updates on new quarantine measures and how their kids were doing with remote learning. My new contacts had never met me outside of my role as (remote) researcher. While they politely accepted my interview invitations, before the interview our relationship remained confined to conversations around scheduling, and afterwards a lack of trust meant that few felt comfortable remaining in touch about the personal interview topics of health and healthcare access. Yet eventually, I found that trying to build trusting relationships virtually – from home – may have a silver lining. This brief reflection considers some of the challenges and opportunities that these dramatically changed circumstances offered.

In February of 2020 I had found myself with promising plans, as many of us did. With two small grants, I was set to spend the summer in a new site in Costa Rica collaborating with a health non-governmental organization (NGO) which provided basic medical care to Nicaraguan migrants. I was also set to make a trip out to an old research site in the Dominican Republic (DR) where I had spent much time collaborating with a different health NGO that provided care to Haitian migrants. It was to be a summer of maintaining and establishing mutual trust via relationship-building.

March of 2020 abruptly altered carefully planned research activities, as scholars suddenly became unable to engage with our research communities as we had typically done. This led us to consider what a pandemic meant not only for our lives and the lives of our families, but also for the world, our research communities, and our proposed projects. We picked up the phone to cancel air travel, wrote emails to funding institutions to request time to submit updated research plans, and called the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ask whether Zoom might be considered an “ethical research tool”. Soon, some scholars suggested that we might create Facebook groups where members could share their day-to-day experiences, and comment on posts from others.

At the beginning of the pandemic, many people were particularly concerned about the lack of doctors in the area. I spoke with Diosmeiry (a pseudonym) on her feelings around the lack of doctors.

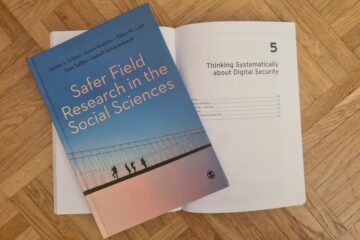

By April of 2020 social scientists had already organized preliminary information on virtual research methods for the pandemic. Researchers suggested Zoom focus groups and interviews; while others asserted that the pandemic was a time for deep dives into the archives, for social media analyses, or to set up Google news alerts to remain up to date on the goings-on around our research sites. Another popular recommendation was to ask a trusted participant in the research community if they might be willing to wear a GoPro camera in order to conduct ethnographic participant observation. Meanwhile, data analysis companies quickly organized remote research trainings centered on the purchasing of their tools. Qualitative coding software NVivo organized a workshop focused on coding social media posts, while statistical analysis software Stata taught a quick course on how to find extant datasets similar to the survey work scholars had planned, and word-processing software Scrivner declared the pandemic a perfect opportunity to get ahead in manuscript writing.

It occurred to me, however, that the focus on providing researchers with ways to continue with our projects and answer our pre-formulated questions unwittingly reinforced traditional researcher-subject roles in which “…the researcher alone contributes the thinking that goes into the project, and the subjects contribute the action or contents to be studied” (Reason, 1994; quoted in Karnielli-Miller et al. 2009). Reinforcing these roles through interacting in virtual space, and the resulting lack of mutual trust, can make for context-lacking research, and improper representation of our research communities.

Being remote, after all, makes us distant in more ways than one. Logistically, Wi-Fi interruptions, a lack of eye contact, and a lack of body language make it difficult to understand the true context of a research site. Interpersonally, if trust is harder to achieve virtually, the true context of a research site is elusive in a different way–a researcher can’t quite achieve the coveted “worm’s eye view” where he or she is able to center the worldview and wisdom of the research participant (see hooks 1991). Questions on personal matters such as one’s health and the health of one’s family are not necessarily topics to be discussed with strangers, and even when these questions are answered, a researcher’s lack of context can mean that a specific piece of information that might be very important for the larger research project is misunderstood. Without broader context, the researcher can unconsciously fill gaps in understanding with his or her own worldview, thereby misrepresenting the research community. In this way, research can become geared more towards the terms of the interviewer and less towards the terms of the interviewee (see Read 2010: 154).

With these hesitations in mind, I attempted nearly all of the above virtual research methods (save the GoPro ethnography). Remote focus groups using the phone to transmit my voice turned me into a hot potato awkwardly passed between participants. Interviews proved to be significantly better, but nonetheless left me feeling that I had only minimal context for my interactions with participants. Google Alerts and social media data collection both proved useful, but still did not yield a worm’s eye view. Throughout, I had remained somewhat dismayed at research prospects without a foundation of trust, which can allow scholars to attempt to address power imbalances in the research process.

Voice notes became an easy way to mutually share daily experiences with changing pandemic rules.

In an effort to maintain trust with research participants with whom I’d worked before, I sent WhatsApp greeting images that are popular throughout Latin America to my established contacts in the Dominican Republic. I had already added Dominican research participants on Facebook and Instagram and now comment more regularly on their posts. When the Dominican elections happened in July, I exchanged hours of WhatsApp voice notes back and forth to learn about the political (and life) changes that were to come. I shared my own frustrations with not being able to leave the house, and listened to their feelings of quarantine restlessness. Mutual sharing felt closer to being in the field. While we weren’t able to enjoy a generously-sugared coffee at sunrise together, or a ride up the mountain on the back of a pick-up truck—we could still share our stories.

As suggested earlier, while maintaining trusting relationships feels more natural to do remotely, without having access to the in-person activities upon which I had previously relied, building trusting relationships virtually remains somewhat elusive. In pre-pandemic times, scholars could visit the homes and families of community members where we conducted research. We could share meals and attend community events alongside interviewees. By constantly being seen in the community, we became familiar and trusted faces. Now, through a screen thousands of miles away, I find it difficult to meet and build confidence with my target population, patients and medical staff, in my new Costa Rican project site.

We may not be able to share meals with our research communities, but we can share cooking lessons virtually!

While there will never truly be an equal replacement for genuine eye contact, some moments can come close. One day during a trip to my home town to visit family, my mother wandered into the room from which I was conducting an interview; what happened next led me to re-frame what working from home might mean to building virtual, trusting relationships. My interviewee stopped mid-sentence and squinted at her computer’s screen: “And who’s that?,” she shouted into the microphone. “That’s my mom,” I responded. My mother excitedly made her way over to the computer to say hello. My interviewee introduced herself, and my mother did too. They chatted for a few minutes, and then my mother exited. The remainder of our interview wasn’t about my interviewee’s health care preferences, or how long it had been since she migrated to Costa Rica. Instead, we talked about our families, and what we were going to eat for dinner. The warm and natural connection made it feel like I was in the field for a moment.

There’s something intimate about seeing into the homes of our colleagues, interviewees, and focus group members during the transition to working from home. We get to meet the children, the pets, the partners, and if we’re lucky, the mothers of the people with whom we are conversing. What better way to build trust?