by: Danny Hirschel-Burns, Yale University

March 2020 was an exciting time for my dissertation research. After two months in Bogotá, Colombia, I made my first trip to my field site of Orillas, Antioquia1, which had experienced more than 30 years of FARC presence prior to the 2016 peace agreement. It was an excellent visit, as the tight-knit social life of the village facilitated both fruitful interviews and numerous introductions. I did not have time to read the news due to my work schedule. Returning to Bogotá five days later, I knew everything had changed. After stress-watching the film Contagion and realizing I could not do my planned fieldwork during a pandemic, I rebooked my flight back to the US as soon as possible. Due to COVID-19, I would not get back to Colombia or Orillas for 18 months.

There were several very strong incentives to transition immediately to digital fieldwork. The pandemic had occurred at the worst possible time for my fieldwork. I was in the second half of my fourth year and just starting the main ethnographic component when it began. As the pandemic rolled on with no end in sight, I seriously considered for the first time that I might not finish my PhD. Additionally, my question, how armed group socialization changes civilian beliefs, is not amenable to non-ethnographic research. There is no reliable data on variation in socialization across Colombia, so I would have to collect that data myself through interviews with combatants and civilians. In short, finishing my planned dissertation required fieldwork, either digital or in-person.

Despite the looming possibility that in-person fieldwork would be impossible for years, I ultimately decided not to perform digital fieldwork in any form. I made this decision for several reasons. First, there would be a rapport deficit. No matter how good one is at digital ethnography, it can never be the same as in-person. Small talk is awkward when using digital technologies, the sound and video will inevitably cut out, and few people want to stick around for a chat once the formal interview is over. Digital interviews are isolated events, whereas when I am in Orillas, the person I interviewed yesterday will say hi to me on the street or invite me over to meet a friend the next day.

This compactness, both socially and physically, of Colombian towns is another crucial factor in which digital fieldwork cannot compare. One becomes known quickly, which rapidly increases one’s ability to recruit new participants through word-of-mouth. I discovered one surprisingly effective research strategy was simply hanging out in Orillas’ main café. Not only did it give me the chance to greet or chat with people I already knew and had interviewed, but a very high percentage of my introductions were facilitated in that space. While I decided that the lack of familiarity and spontaneity created by digital fieldwork was reason enough to not do it in Orillas, the problem would have been even more severe in the two other field sites that will be included in my dissertation. Trying to start at a new field site digitally, without having ever gone in-person, was an insurmountable task.

A third reason is that in-person ethnographic fieldwork provides an incomparable sense of place for locations and themes about which it is difficult to learn about digitally. The geography of Orillas is very rough, and few roads appear on maps. Without being there in-person, there is no way to see important places and where participants live, or to really understand the physical and social geographies that are so crucial to ethnographic work. Perhaps even more devastatingly, participant observation becomes an impossibility with digital fieldwork in places where associational life was not moved to Zoom.

A third reason is that in-person ethnographic fieldwork provides an incomparable sense of place for locations and themes about which it is difficult to learn about digitally. The geography of Orillas is very rough, and few roads appear on maps. Without being there in-person, there is no way to see important places and where participants live, or to really understand the physical and social geographies that are so crucial to ethnographic work. Perhaps even more devastatingly, participant observation becomes an impossibility with digital fieldwork in places where associational life was not moved to Zoom.

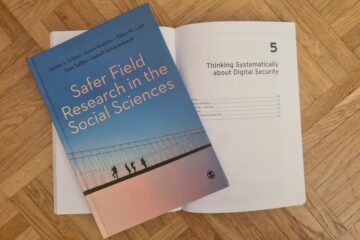

Finally, and most importantly, I had serious ethical concerns about digital fieldwork. The nature of my project means asking sensitive questions. For in-person fieldwork, handwriting notes, not recording interviews, and thinking carefully about where the interview is taking place all helps improve security for myself and my participants. Doing fieldwork digitally means I lose control over all of those elements. If I had done fieldwork digitally, inevitably it would have been over Whatsapp, the dominant mode of communication in rural Colombia. As a researcher without a strong background in technology, I did not feel like I could guarantee to myself or my participants that Facebook’s encryption promises meant no one else would access our interviews. Alternatively, I could have used a more secure platform like Signal, but this likely would have involved asking participants to download and use an app they were unfamiliar with. This would have introduced an unfortunate bias in my research, where it would have been difficult to reach older, less technologically-savvy residents of Orillas, who also tend to be the people with the best sense of local history. Especially when Orillas’ residents were dealing with a local pandemic that saw test positivity rates exceed 30% on occasion, asking them to jump through hoops for my research felt wrong.

I want to be clear that I am not arguing digital fieldwork is uniformly bad idea. Indeed, I worked on a co-authored project during the pandemic that involved digital interviews with primarily rural Colombian participants. There were several key differences. First, all the respondents were already known to my co-author, Andrés Aponte, who conducted the interviews. Second, while we did ask about violence, most of the questions focused on factual issues, like what armed groups exercised territorial control or what aspects of life they regulated. Third, all respondents were former armed group commanders, local leaders, or researchers: in other words, people who were used to talking publicly about the communities they lived in or knew well. We did not collect names at any point, and therefore even I do not know the names of the people my co-author Andrés interviewed. Together, these conditions allowed for our digital fieldwork to be feasible, useful, and ethical.

On the whole, the sensitive nature of my dissertation project and its rural setting produced overwhelming logistical, methodological, and ethical quandaries. While there were compelling reasons for me to transition my fieldwork to digital as soon as the pandemic started, digital fieldwork would have harmed the quality of my ethnography and been at best borderline ethical. Just as a crucial skill in qualitative fieldwork is knowing when to stop gathering data, it is important to recognize when circumstances beyond one’s control demand stopping research.