Beginning in the last week of January 2020, I nonchalantly followed world news from the TV screen at my gym in Arlington, VA about a virus outbreak in China. I did not seem to be bothered much about the happenings. After all, media discussions made it seem distant from the rest of the world. I was in the second semester of my third-year doctoral program in History and right in the middle of my comprehensive exams. My written major field exams were scheduled for March 11, 2020, with an oral examination to follow up two weeks after that date. I had scheduled my written exams over spring break in order to avoid juggling TA duties with comps. Over that spring break, things went south for everybody. Our world as we knew it was about to change for a long time. By the day I received my exam questions, we already knew in-person teaching was suspended at Georgetown until further notice. Corresponding with my academic mentor that weekend, she aptly described the time as ‘‘the most tumultuous three days on campus in 20 years.’’ This unprecedented experience as a graduate student during a pandemic would go beyond the distracting 72 hours of my comps.

Prior to attaining candidacy by the end of the spring semester, I had been concerned with how the global health situation would affect my imminent fieldwork trip originally scheduled for the 2020/2021 school year, to be conducted mostly in Ghana. The West African nation went into a partial lockdown in April 2020. Geographically, the lockdown was limited to the capital of Accra, identified as a hotspot for transmission. I watched with concern as events unfolded in the country I call home and my research field site, as land, sea, and air borders were closed, various institutions shut down, internal movements were restricted, and sections of the city were cordoned off with a visible presence of security forces. Overall, Ghana was hailed for tackling the virus almost immediately and head on. Two weeks later, the initial lockdown was called off and replaced by a shift working system for most institutions, including the national archives. This relaxation notwithstanding, all CoVID 19 protocols were to be adhered to and the country’s borders remained closed indefinitely. This was to remain until September 2020.

I was anguished because while the archives remained open in the country, there was no way I could travel there. The only way to get out of the US was through periodic evacuation flights organized through the Ghanaian Embassy and High Commission in DC and New York respectively. However, I did not qualify to be evacuated since the exercise was targeted at Ghanaians stranded in the US and urgently needed to return home. I was anguished about the entire experience especially because the availability of relevant digitized materials for my research- a history of Indian business in twentieth century Ghana- is nonexistent.

The PRAAD building in Accra. Photo by author

The Ghana national archive, known as the Public Records and Archives Administration Department (PRAAD) is a colonial archive with its headquarters in the capital of Accra. In addition, there are regional offices in Koforidua, Kumasi, Sekondi, Cape Coast, Sunyani, Ho, and Tamale. The Accra office houses the largest collection of documents on Gold Coast and independent Ghana’s history, while the other branches house region specific materials. Some of the materials found in PRAAD include colonial administration files, files from the colonial secretary’s office, various ministerial records, court records, and native affairs documents. More often than not, researchers complement materials here with others from metropolitan, missionary, and corporate archives. Unfortunately, this national archive is not fully digitized. Where such digitized collections exists, they are from individual searchers who painstakingly scan materials relevant to their research and make it accessible to others, all within a particular network. To conduct research in any PRAAD branch requires one’s physical presence to go through finding aids and requesting for specific folders along the way. On some days (and at some branches), you are told you can request only three folders at a time. On other days, you can request for more than three. You need to read the atmosphere and the staff attending to you to take this gamble. Some days you can get all the documents you request. Other days, some of your requests turn out to be missing, damaged, or misfiled. This notwithstanding, working in a non-digitized archive like PRAAD comes with its own perks. Over the years, you grow to love it, even as frustrating as it gets. While some staff are young university graduates performing their national service to the state and eventually move on, others are permanent staff who become familiar faces and useful guides as time goes by.

As I spent my fall semester teaching virtually in Georgetown, I thought of two ways I could remotely access the archive. The first was by soliciting for materials already collected by other users of the archive. This network, for me, included an immediate circle of fellow Ghanaian graduate students as well as Ghana Studies Association (GSA) members with overlapping research interests, all of whom I could reach via WhatsApp chats, Facebook posts, and email. This notwithstanding, I knew that there was a slim chance of getting substantive assistance related specifically to what I was looking for due to how different everyone’s research interest is. In the end, I never got around to ask. On hindsight, I should have asked since a member of my dissertation committee recently shared with me a relevant file she had come across from her time in PRAAD.

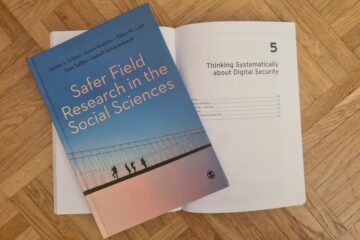

Notice on use of gadgets in the PRAAD. Photo by author

The second option was to solicit for help from a colleague studying at the University of Ghana. However, she pointed out to me that PRAAD-Accra was no longer allowing the use of personal devices, beginning August 2020, due to an altercation with a patron. Prior to this, one paid a daily fee to take unlimited images/scans with a personal device. Barely a few weeks later, they again allowed the use of personal devices, but now at an extremely high charge of paying by the page and under the scrutiny of a staff. Ultimately, my attempt to remotely access the archive was unsuccessful as my research assistant disliked this new policy and clearly did not want to patronize them. To the best of my knowledge, the incident that led to the changes in scanning policy in the Accra archive had nothing to do with the pandemic. However, the ‘‘orders from above’’ constrained my efforts to access the archive remotely.

I managed to travel to Ghana in December 2020 to see how best I could start my delayed fieldwork. Prior to this time, air travel restrictions had been lifted in September on conditions that travelers be in possession of a negative PCR test result taken no more than 72 hours before take-off, in addition to undergoing a second test upon arrival in Accra at the cost of $150. I went through the entire procedure and arrived in the country on December 7. On my way home, the principal street running from the airport through to my residence was unusually quiet for an election night. The calm atmosphere meant different things for supporters of the two major political parties. I, on the other hand, was excited to be back home to see familiar faces and commence field research. I was aware that unlike other countries, the national archives here was opened and this was good news.

Example of a “thick” document. Photo by author

My experience working in some branches of PRAAD between January and April has shown that even though the archive is open, I am still burdened with the challenge of doing research in a pandemic. For starters, to ensure that there is physical distancing within the search room, the numbers of daily staff have been reduced. For instance, in Accra I have counted between 4-7 staff in the search room, 3 in Koforidua, and 2 in Sekondi at a time. While I am not aware of any limit to the number of visitors admitted in a day, on the busiest day since I have been in Accra, visitors have been no more than seven at a time. The same goes for Sekondi and Koforidua. The limited number of staff at the archive means that the retrieval process is much slower than in normal times, with lots of wait time. During such wait times, I pick a stroll, doodle, or just stare at nothing in particular in the search room. Moreover, in Accra, in order to not put too much pressure on the staff there is now a limit on the total number of documents you can request in a single day. For example, one can request only about 10 thick documents like Supreme Court cases from early colonial periods, while for flat folders, one is allowed up to 20-25. I only know what constitutes ‘‘thick’’ versus ‘‘flat’’ documents because the archivist pointed at them in the search room. It is also worth noting that no retrieval requests are accepted after 3pm and while this is an existing policy, this, combined with the new measures have constrained the pace with which I would like to move with archival research.

In addition, limiting the number of employees in the archive takes the form of a system whereby the staff is divided into two groups that work every other week. Due to this rotation system, I have encountered two distinct sets of PRAAD staff over the past months. One set is usually accommodating with my rapid requests, fast with the retrieval process, and generally very efficient to work with. In one of the regional branches, they explained to me how 10 out of 15 materials I requested were being held somewhere else and I could potentially access those once they relocated to a new building in one to two months. This obliging group would ask that I write all my requests for the day, pull them out to the search room, and give them to me one at a time. By doing this, they conformed to the policy of working on one document at a time but with some flexibility that made me work faster. The other set were the opposite and it was frustrating dealing with them on a bi-weekly basis. On one occasion, I was asked to return the next day for my final document of that day and it was just 1pm in the afternoon. The day before this, search and retrieval had ended around the same time because it got dark and cloudy and there was not enough lighting in the retrieval room. I was fortunate to spend my time in one of the branches with a colleague from Basel who shared a similar experience about other branches. To avoid going through what he experienced there, he put me in touch with a member of the accommodating group so I know their schedule and plan my trip there accordingly. The challenge with this is that, assuming I plan to use that archive for four weeks, I can anticipate two weeks of productive work done with one set of staff and only hope for the best on the other two weeks with the other set.

Any researcher to PRAAD now and in the coming months may have similar experiences regarding policy changes as I have. However, I must confess that the new fees for taking images on personal devices comes at a huge cost to students studying locally. I studied in Ghana for a Masters’ degree and know that the average Ghanaian student receives no financial support for research. It will be considerate of PRAAD-Accra to review this policy, at least for students studying in local institutions.

Overall, my challenges in conducting archival research in Ghana seem to be slightly better than in other countries, for which I am grateful. I know this because as part of field research, I was supposed to visit the corporate archive of Unilever in Port Sunlight, Liverpool, which remains closed indefinitely. While I consider using business records an important aspect of my methodology and contribution, I am afraid I may not be able to utilize these materials due to the limitations on the time to finish my degree.

I also have experienced firsthand the difficulty in conducting oral history during these times due to public health concerns. Moreover, in my opinion, social customs guiding interactions in Ghana makes it inappropriate for me to hold telephone conversations with respondents such as the aged and market women. Thus, I have had to put this aspect of my research on hold.

As more people get fully vaccinated in Ghana by summer, including myself, I feel confident about reaching out to people and scheduling in-person conversations, while adhering to CoVID protocols. I acknowledge and recognize that I am not alone getting research done during a pandemic. And I stand in solidarity with each and everyone of us in academia going through this experience from different parts of the world. It will get better.